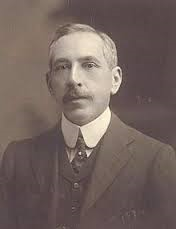

Hon. Billy Hughes - Prime Minister of Australia 1914

Hon. Billy Hughes - Prime Minister of Australia 1914THE GANGE - MALTESE SHIP - 1916

'IT-TFAL TA’ BILLY HUGHES'

'THE CHILDREN OF BILLY HUGHES'

In 1808, Sir Walter Scott famously declared in a poem: 'Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!' The message about deception and its complications could very well have been written about the 'dictation test', Australia's principal method of excluding unwanted migrants during the first decades of the twentieth century .

In 1916, the test, which could be applied against selected arrivals in any European language, was used to exclude a group of Maltese labourers. Two hundred and eight of the men on the French ship, Gange, were tested in the Dutch language. They failed, and became prohibited immigrants. Yet they had paid their own fares, traveled on British passports and had no idea that they would be excluded.

During its 58 year history, the test variously had racial, political and even moral applications.

This is a sad story how it came to be that the British subjects from Malta were stopped from disembarking at Sydney and forced to travel on to New Caledonia. From there, the story became a tangled web of politics, prejudice and bureaucratic practice. Read on to learn the eventual fate of these men.

On 29 October in 1916, a group of 208 Maltese labourers was subjected to the notorious 'dictation test' provision of the Immigration Act and declared prohibited immigrants.

Under section 3 (a) of the Act, any person seeking admission into Australia could be stopped from disembarking if they failed a dictation test in any European language.

The Maltese were given the test in the Dutch language and, on failing the test, were compelled to remain on the French mail-boat, Gange, on which they traveled until it reached its final destination, New Caledonia.

It was a bizarre situation: a boatload of British subjects (the Maltese were British subjects by birth) on a French vessel, being kept out of Australia, technically, because they could not understand the Dutch language.

The men were stranded at Noumea for about two months. Their families in Malta came close to starvation, as they were dependent on the wages their men-folk would have earned in Australia. Many of the men had sold their goods in Malta or gone into debt to raise the fare to Australia.

The Maltese had been attracted to Australia by the prospect of the high wages to be earned for such hard pick-and-shovel work as railway construction in New South Wales and mining in Tasmania.

There was a very small Maltese settlement in Melbourne at the time, mainly based around a boarding house run by John Rizzo. Mr Rizzo would greet his countrymen, put them up at his King Street residence, and send them off to the Mount Lyell Mining Company headquarters in Melbourne.

|

From there, the eager Maltese would make the journey to dank and rugged Queenstown, Tasmania, where the company owned the biggest copper mine in the British Empire. They quickly earned a reputation as reliable and diligent workers.

The Maltese passengers on the Gange were eventually allowed to return to Australia, leaving Noumea for Sydney on the St Louis in mid-January, 1917.

A new nightmare began for them, however, when - far from being allowed to disembark at Circular Quay - they found themselves transferred to an old hulk (an old ship, permanently moored), the Anglian, in Berry's Bay. They were detained under armed guard. A few sought the only way out, and dived into the harbour. Most were captured on shore and returned to the hulk.

|

After much public controversy, and a fair amount of pressure on Prime Minister Billy Hughes, the Maltese were finally allowed to disembark from the hulk on 9 March, 1917, roughly four months after the Gange was supposed to have disembarked them at Sydney. The experience had been an agonizing and ruinous one for the men who were innocent victims of Australia's immigration philosophy. An official of the Colonial Office in London angrily scrawled the following words on a document relating to the incident: 'An act of gross injustice, carried out under a mockery of legality, worthy of the Germans'. (Handwritten note by Mr. Ellis, Colonial Office, London, on cover of CO file 'Maltese Emigrants', PRO CO418/158/4575)

The Gange had arrived in Australian waters at a time when the nation was bitterly torn over the issue of conscription for overseas service during World War 1.

Malta's position in the war had already earned the tiny archipelago the title of 'Nurse of the Mediterranean'. Thousands of wounded ANZACs had recuperated at Malta, and the entire island of Malta had virtually been transformed into a base hospital.

|

Moreover, the Maltese had actively served in the war. There are 600 names on Malta's War Memorial of Maltese who fell while fighting for the British Empire. There were six Maltese members of the 7th Australian Brigade which earned fame for the Gallipoli landing. The majority of men on the Gange were ex-servicemen; most had served at Gallipoli with the Malta Labour Corps.

In their shared service to the Empire, the war had brought Malta and Australia closer together. A telegram sent by an ANZAC convalescent in Malta to his home in Australia summed up the feeling. It read simply, 'Wounded in foot, am in Heaven in Malta'. (Daily Malta Chronicle, 10 May 1915) Another convalescent declared in a letter to the Maltese press, 'We will carry back to Australia the kindly remembrances and undying gratitude which time can never efface'. (Daily Malta Chronicle, 4 August 1915)

The Gange incident, however, revealed that Malta's war-time hospitality and membership of the British Empire took second place to considerations of domestic politics and the concept of White Australia.

Victims of White Australia

The timing of the Gange's arrival at Melbourne could not have been less opportune. The vessel was scheduled to berth at Melbourne on 28 October, the very date on which Australians were to vote in a national referendum on the conscription issue.

The opponents of conscription, especially those in the labour movement, had argued all along that, if conscription was introduced, 'white' Australian workers who served overseas as soldiers would be replaced by imported, 'cheap', 'coloured' labour: 'coloured job jumpers'. Living standards and wage rates would be reduced to the benefit of the capitalist class, and the vision of a White Australia would be lost. (The Brisbane Worker, 12 October 1916)

Those who supported conscription were no less dedicated to a White Australia. They argued that unless the Empire won the war, the Kaiser would dictate eventual peace terms, and the White Australia policy would remain only if it were suitable to Germany.

It was against this backdrop, often marked by bitter and sometimes violent debate, that the Gange had arrived off the coast of Western Australia in mid-October. The anti-conscriptionists were delighted by the arrival of such 'evidence' of their 'cheap labour' claims. Indeed, many years later, the Labor tyro Jack Lang would recall in his memoirs, 'It was just the evidence we needed'.

Despite Prime Minister Hughes' attempts to have the Chief Censor impose a 'prohibited publication' ruling concerning the Gange's arrival, the anti-conscriptionists were kept well posted by leaks from within the telegraphic service.

Frank Anstey's column in Labour Call was embarrassingly accurate in exposing the movements of the vessel and its human cargo. Thus, the Gange posed a threat to Hughes' referendum.

The Prime Minister, a staunch advocate of conscription, had given several guarantees against the importation of so-called cheap foreign labour after earlier arrivals of unskilled migrants from Southern Europe, including Maltese.

In light of the Gange's imminent arrival, carrying the largest single group of Maltese migrants ever to come to Australia, Prime Minister Hughes became desperate. The boat simply had to be stopped, and the dictation test was the most effective way, within the immigration law, of stopping these men from disembarking.

To achieve his objective of stopping the ship's arrival at Melbourne on 28 October, Hughes had to engage in some international manoeuvres. He had to rely on the cooperation of the French Consul-General in Sydney and the French captain of the Gange. Most importantly, he had to notify the British Secretary of State for Colonies, at the Colonial Office in London, of his plan.

On 9 October, at Hughes' behest, the Australian Governor-General, Ronald Munro-Ferguson cabled the Secretary of State assuring him that the referendum would 'be killed' if the ship arrived at Melbourne before the 28th. It would be 'a great national disaster', he said.

The Governor-General's cable threw the Colonial Office into chaos. If the Australian prime minister was suggesting that the British Government should somehow interfere with the passage of a French ship then he was implying a course of action that bristled with dangers. The Colonial Office had to put Imperial interests first.

While Great Britain wanted additional Australian troops (conscripts), it also needed to maintain good relations with its ally, France. The principal purpose of the Gange's voyage was to collect French reinforcements from Noumea.

On 18 October, Hughes issued a public statement repudiating the 'wicked inventions' of the anti-conscriptionists and reiterating his pledge that no cheap labour would be admitted into Australia during the war. He conceded that '200 Maltese' were on their way on the Gange but stated that 'no coloured labour would be admitted'.

Hughes' acceptance of the Maltese as 'coloured labour' infuriated the British Colonial Office but, from the pro-conscription point of view, this was a necessary political gesture for an Australian audience.

As inevitably happens in a situation characterized by suspicion and prejudice, rumours abounded concerning the magnitude of Maltese immigration. More than 2500 Maltese were said to be working on the Trans-continental Railway, while hundreds were allegedly disembarking from boats at Coffs Harbour. Hughes repudiated both falsehoods in the Argus newspaper (25 October, 1916), indicating the extent to which he took them seriously. At a referendum meeting at Inverell, one speaker informed the protest gathering that 4000 Maltese had just landed. Respectable citizens started discussing the 'Maltese invasion'. It was a lot of fuss and panic, given that there were roughly a thousand Maltese in all of Australia, and only 212,000 in Malta itself.

The eventual prohibition of the Gange Maltese provoked protests from ex-servicemen who had recuperated at Malta and from supporters of Maltese immigration, such as the head of the Millions Club, Arthur Rickard, who condemned the detention of the Maltese on the hulk in Berry's Bay as 'an outstanding example of man's inhumanity to man'. (SMH, 28 February 1917)

The Maltese-born Governor of New South Wales, Gerald Strickland, worked behind the scenes to support the Gange men and the Maltese were also fortunate to have a Maltese priest based in Sydney who acted tirelessly on their behalf. Father William Bonnet who had arrived from Malta in January, 1916, pleaded the Maltese case to both the Prime Minister and Governor-General.

His argument was concise and logical: the Maltese had left Malta on the Gange, with their British passports endorsed, before Hughes' imposition of restrictions on 'imported labour'; the use of the dictation test had been dishonest, as Hughes had already publicly stated that the Maltese would be excluded from Australia; several of the men carried excellent references from British military authorities at Lemnos, Mudros and Gallipoli and the families of the men had been 'absolutely ruined' by the loss of income from their breadwinners.

Moreover, the Gange Maltese were free immigrants and not contracted labourers. They had paid their own fares. The Maltese had a good record for joining trade unions in Australia. They were loyal to the Empire; indeed Maltese interest in Australia had been accentuated by close contact with wounded Anzacs who had been shown great kindness in Malta.

The pro-Maltese argument proved irresistible during the period in early 1917 when the men's miserable condition as detainees on the old hulk in Berry's Bay aroused public sympathy. At that point, what was to be gained in keeping them out? The Prime Minister had been defeated in his referendum; the people had rejected conscription for overseas service.

Hughes had arranged with British Imperial authorities to ensure that no passports allowing travel to Australia would be issued to men of military age from Malta, the British Dominions or the United Kingdom itself.

Perhaps the issue was resolved in the men's favour for purely practical reasons: the wartime shortage of shipping meant that deportation would not be easy. On 9 March, the men were released from the hulk and quickly recruited by employers.

The biggest group went to the Mount Lyell mines. Others laboured on railways and wharves around New South Wales. A few established market gardens in Sydney's outer west. Small groups worked on the Burrinjuck dam project near Yass. A few ventured north to the Queensland sugar district around Mackay.

Generally, they tended to move around in small groups, taking any available unskilled work, and led by whoever in the group could best speak English.

The Gange episode, like any highly dramatic moment in history, became mythologised.

For many years, William Morris Hughes was taunted by his opponents with the nickname William 'Maltese' Hughes. The nickname may have been coined by Labour Call in its 23 November 1916 edition